The Power of Inclusive Language – A Recap

The words we use carry meaning and power.

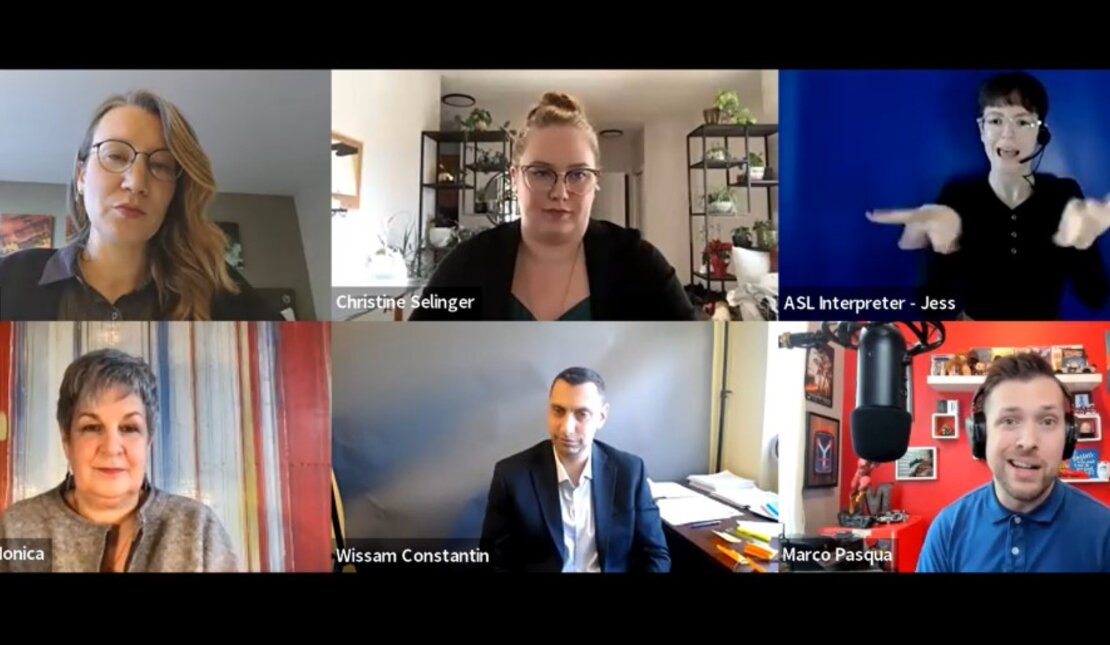

This was the theme of our live discussion, The Power of Inclusive Language, held for International Day of Persons with Disabilities on Dec. 3, 2021. The panel of accessibility and inclusion experts from across Canada offered plenty of food for thought during the hour-long conversation that was moderated by disability advocate Marco Pasqua.

If you missed the event or want to share it with colleagues, family, or friends, you can watch the recording here.

The conversation featured the following line-up of panelists:

- Christine Selinger, Instructional Designer with Canadian Blood Services, Director of Education and Events for the Abilities Expo and an independent consultant advising on accessible event solutions

- Meghan Kelley, National Manager, Business Solutions, Canadian Council on Rehabilitation and Work

- Monica Ackermann, Director, Enterprise Accessibility, Scotiabank

- Wissam Constantin, President, Canadian Association of the Deaf

There are so many points of discussion around the topic of inclusive language. While this post is a recap of the event, we will email registrants answers to the top-three questions from the Q&A period that time did not allow for addressing.

Panelists all agreed that inclusive language comes down to being mindful. When we do our best to communicate thoughtfully, and with intention, we are promoting equity and advancing social progress for people with disabilities. Panelists also agreed inclusive language is not about simply using a list of ‘correct’ words.

“A list of words doesn’t change anything; attitude is what will make a difference,” said Constantin. “A person can say all the right words and still not have the right approach, the right tone, or the right attitude.”

The following questions sparked a thoughtful and engaging conversation:

What does disability-inclusive language mean to you?

For Ackermann, disability-inclusive language acknowledges that disability is about an individual’s lived experience thus should be treated accordingly. It is also not about depicting people with disabilities as heroes to be admired or victims to be pitied.

“For me, disability-inclusive language is really about putting the person first; it’s being human-centered, and acknowledging that disability is an individual’s lived experience and an integral part of a person with the identity,” Ackermann said. “Inclusive language really goes beyond the phrase used to describe a disability. Does the language perpetuate bias and stereotypes? Does it celebrate both the uniqueness and everydayness of the human experience? These, to me, are some of the inclusion decisions that we are empowered to make each and every day.”

Kelley added that inclusive language is ever-evolving, is nuanced, and reflects personal preference.

“Language evolves over time, and the context and understanding of it that we have today will change as we learn as we grow,” she said. “Respect the others around us and the choice in terms of language they choose when it comes to identity.”

This also includes understanding the preference for person-first language, which puts an individual before their diagnosis, or identity-first language, which is language that leads with a person’s disability, noted Selinger.

“I identify as a disabled person, specifically putting disabled first as I am a wheelchair user. To me, inclusive language across the board is both thoughtful and deliberate,” she said. “I know language is difficult to change. Things will come out of your mouth before you realize what you’ve said – I’m definitely guilty of that! We’re not here today to tell you that what you’re doing is wrong or that you’re a bad person if you use certain language. We’re here to provide awareness of the impacts of language.”

What are some inclusive communication considerations from a pan-disability lens?

It’s essential to consider the whole population when considering inclusive language, said Selinger.

“When we’re thinking about language and disability, we need to think beyond mobility aids and beyond people who use wheelchairs. Disabilities aren’t segmented, so when thinking about one disability, you can’t just exclude others.”

Communication methods have changed during the last 18 months, pointed out Kelley. Health restrictions brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic have resulted in virtual meetings being the new normal for the office. The onus is on organizations and service providers to recognize gaps in accessibility and provide solutions within the digital realm, Kelley added.

Constantin stressed that disability-inclusive language is an individual preference, and there is a world of preference within a specific disability.

“I’ll use my disability, for example. Within the D/deaf culture, there’s a variety; people who prefer lip-reading, people who prefer signing, or reading and writing, and people who prefer to use an interpreter,” he said. “If you have one experience with one disabled person, it doesn’t mean all disabled people are going to be like that one person.”

Is there a time you experienced inclusive language, and what impact did it have on you?

Ackermann, who acknowledged she speaks as an ally, said she is heartened when she witnesses others make disability-inclusive language part of their vocabulary and work as it does a lot to contribute to a cultural shift.

Selinger used two examples to support Ackermann’s statement. She is used to organizations being caught off guard when she calls ahead of time to ask about their building’s accessibility. Once, she called a pub where the employee rattled off a list of meaningful accessibility features.

“I was totally unprepared for somebody else to be prepared for the question!” Selinger said. “So, for anybody who runs a business, be prepared for the questions and have answers. It was so wonderful to recognize that this place knew the things that needed to be accessible.”

She recalled another instance, at a funeral, where the officiant requested everybody to stand if they were able. “It was so tremendously impactful because it included me,” Selinger said. “There are lots of little ways to include disability in your everyday language.”

How can we be an advocate in our workplaces for inclusive language?

It’s vital that everybody – those with disabilities and those without – learn from one another, according to Constantin.

“I’ve heard it said that people with disabilities are not born to live; they’re born to advocate. I think that’s absolutely unfortunate and true because we spend so much of our daily energy educating and explaining what our needs are,” he said.

“People who have power in the workplace need to be cognizant of asking people with disabilities how they can be accommodated. It is also a necessity for a person with disabilities, when they encounter disabilities, to say how they can be accommodated. I believe that working together, we’re able to make the world better.”

Employers can also lead by example by providing opportunities for dialogue and education, Kelley said. It’s also important to be aware of ableist perspectives, added Ackermann.

“So often I’ll hear ‘the disabled employee is struggling to keep up with the productivity demands of the job.’ That’s a really ablest perspective. It’s not the disability that’s at the root of the struggle. If you want to call it that,” Ackermann continued, “it’s the accessibility barriers in the workplace. We really have to be conscious about how we frame these conversations. And in these conversations, too often, I see and hear the words “issue,” “problem,” “concern” in the same sentences as “disability.” I don’t think it’s done maliciously or intentionally or to cause harm, but it is doing harm.”

Closing thoughts on The Power of Inclusive Language

Kelley: “If there’s a last statement that I want to ensure that I left the participants of this event with, it would be the importance of choice when it comes to language. Oftentimes we are asking individuals to identify or to speak to their identity, rather than asking them to come as they are.”

Ackermann: “We may have a common goal, but we’re all coming at it really differently. I think that the more opportunities we have to have this dialogue will make our community and conversations much richer.”

Selinger: “When it comes to language, etiquette, and anything around disability, the people to listen to are people with disabilities. “There is no one size fits all. Make sure that when you’re engaging with individuals that you’re finding out what their preferences are when you’re talking to them.”

Constantin: “I advocate for companies to hire and pay for interpreters. Companies that are sometimes not willing to pay for interpreters, I have to ask – do you make people who use wheelchairs pay for wheelchair ramps? I want to just put companies and businesses on notice for their employees that, you know, you’re providing access, and it’s not our responsibility to provide the access. Asking doesn’t hurt. People are generally not going to be offended if you ask them what they need.”

The Rick Hansen Foundation is honoured to have hosted this incredible conversation for IDPWD and we look forward to continuing it in future discussions. A sincere thank you to our valued panelists for sharing their experiences and thoughts, as well as to the many attendees for being a part of the conversation. Only together can we work towards creating an inclusive society where people of all abilities are seen as equals and have the opportunity to live life to the fullest.

Because, as Constantin pointed out:

“Disability itself is so often framed in the wrong way, it’s seen as what a person can’t do. And I would just like to say that we are just functioning in a different way. And that that’s all. It’s just a different perspective, a different way of being. No one way of being is better than another. It’s just a different way.”