Youth Exchange: Disability and Social Justice – A Recap

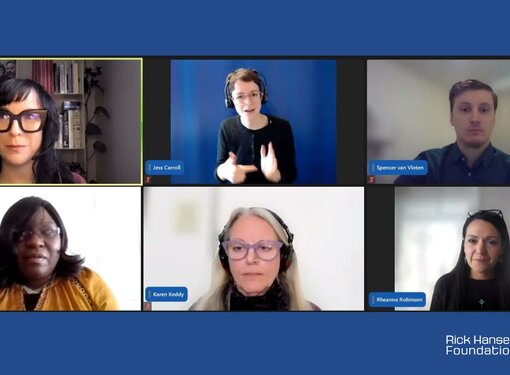

In honour of International Day of Persons with Disabilities, which takes place annually on December 3rd, the Rick Hansen Foundation School Program (RHFSP) virtually brought together members from RHFSP’s Youth Leadership Committee to discuss topics such as social justice and the social model of disability. This hour long, interactive conversation was moderated by Mihai Covaser, a youth leader who has lived experience as a person living with cerebral palsy (CP). Shortly after his family immigrated to Canada, Covaser began working with a variety of organizations as an advocate, fundraiser, event organizer, and, most recently, committee chair for the Youth Leadership Committee.

The four panelists brought their unique experiences, perspectives and thought-provoking dialogue to the discussion:

- Alexis Holmgren – Alexis is a youth changemaker, rare disease patient advocate, 2021 RHFSP Difference Maker of the Year award recipient and published writer from Red Deer, Alberta. She has been a passionate advocate for diversity, inclusion, and accessibility from the age of 12, drawing from her personal experience as a young person living with multiple life-threatening rare genetic disorders to create change for a more inclusive and accessible world.

- James Kwinecki – James is studying Sociology and Social Justice Studies at the University of Victoria. Currently, he training as a Paralympic hopeful for 2024 in Para Rowing. James lost his vision at the age of 21 and had to relearn what it means to participate in sports. He is passionate about advocating for accessibility and inclusion.

- Élise Doucet - Élise is a young Deaf adult who is passionate about Deaf and climate activism. She is an alumnus of the Fraser Basin Council’s Co-Creating a Sustainable BC initiative, was a Youth Observer at the Adaptation Canada conference 2020, and was a Youth Delegate at the Rick Hansen Youth Leadership Summit 2017. One of Élise’s activism projects include working with her local government to put closed captioning on city council meeting videos.

- Maggie Manning – Maggie is an advocate for accessibility and inclusion of people with disabilities, which stems from her lived experience as a person living with a physical mobility disability and chronic illness. She has been recognized with the Terry Fox Humanitarian Award for her efforts, and currently serves on the International Disability Alliance Youth Caucus. Her ultimate goal is to share her story with others to help create universal understanding and acceptance of people with disabilities.

The Culture of Disability

The four panelists shared their perspectives on whether they describe disability as a culture and what it means to them.

“I one hundred percent agree that it is a culture,” says Manning. “Sometimes I don’t feel understood by my friends and family, my peers. And that’s because I’ve had a very different experience growing up with a disability.”

Manning adds that she feels a strong sense of culture through competing in parasport.

“I get to go to these events where it is all people with disabilities and I look forward to that because I know that there’s this underlying understanding between us,” she says.

Kwinecki furthered Manning’s perspective on culture in parasport, commenting, “The disability culture is very strong, and I think nobody really understands it unless they have a disability. The disabilities can be so broad, but we all come together with some sort of commonality.”

Doucet pointed out the prominence of Deaf culture, including the Canadian Cultural Society of the Deaf and the vast array of sign languages, as well as the numerous traditions, stories, and cultural norms that exist within the Deaf community.

“As soon as I am around other d/Deaf people or other disabled people, there’s a lot more of that innate understanding,” she says. “They get it.”

The panelists also acknowledged that disability culture is not necessarily something all persons with disabilities feel connected to. Holmgren shared that as a person who lives with rare diseases, her experience is different and often not fully understood by others in the disability community.

“I don’t necessarily find that common sense of understanding. So, I think for me... I don’t see [disability] as a whole as a culture, I see it more as a community with common goals or even as a human rights movement,” Holmgren says.

The Social Model of Disability

There are generally two dominant models in which disability is perceived by society—the medical model and the social model. The medical model, Covaser explains, “is described as a medical condition...with symptoms that may or may not be treatable.”

The social model is reflective of the social and physical barriers that prevent persons with disabilities from fully participating in society.

“For me, this really hits home,” Kwinecki says. “I lost my vision at the age 21, so I got to go through school with 20/20 vision and no barriers whatsoever. Now I’m in postsecondary school trying to navigate these [new] ways of being a student.”

Kwinecki continues by saying that if the education system—from primary to postsecondary—integrated the social model of disability into curriculum from the beginning, it would improve the entire education stream for teachers, faculty and students, including folks with invisible disabilities and those who do not identify as having a disability.

This comment sparked an interesting conversation among the panelists.

“There’s this big debate on whether putting a label on yourself is a bad thing,” Manning says. “For me, I don’t look at it as a label. It’s more me being proud of who I am and that my disability is a part of me. Ultimately for me, the social model of disability is less about focusing on the person’s disability and what it prevents people from doing, and more so focuses on ways to break down those barriers to ensure everyone has equal access universally.”

Impactful Advocacy Comes in Acts That Are Big and Small

The panelists shared the ways they advocate for greater accessibility in their communities.

Holmgren shares that her lived experience motivated her to make her local pool more accessible for folks with sun allergies and sensitivities. The project included putting an ultra-violet light blocking film on the pool windows and led to her receiving a Difference Maker of the Year award in 2021.

“I applied for a very, very competitive federal grant and worked with my city on this, which got approval in March 2020. [Because of the COVID-19 pandemic] the project had a few delays, but was finished that summer,” she explains. “I actually had a couple of people private message me saying they couldn’t believe this was something someone was doing, and now they were actually going to be able to use the pool for the first time.”

Holmgren says that positively impacting people’s lives is exactly why she continues her work as an advocate.

Doucet reminded everyone that meaningful advocacy can stem from both big and small acts. She shares how the present-day d/Deaf and hard of hearing community do not typically use the term “hearing impaired.” When she noticed this language was still being used on the Canadian government website, she sent them an email asking for the language to be updated.

“Two weeks later, they changed the wording,” she says.

Kwinecki adds that language choice is not one-size-fits-all, and what may be the preferred language for one community or individual may not feel appropriate for others.

“It’s interesting, throughout the 20th century, the blind and visually impaired community steered away from using the word ‘blind,’ because blind infers someone can’t see anything at all, and moved towards the term visually-impaired. I would say most of the community I interact with uses the term ‘visually impaired,’” he shares.

Kwinecki says that through his own lived experience navigating his university campus, he has been able to bring recommendations and change to the University of Victoria

Manning closes the topic by saying that for her, advocacy comes in the form of sharing her story and encouraging others to make a difference.

“At the end of the day it doesn’t matter who it is, if they want to make a difference, that’s all that matters,” she says.

The audience was then welcomed to join the conversation. They were asked, "What are the steps you are going to take to be an advocate?" A variety of action items were added to the discussion, including:

- Listen to people’s experiences and the barriers they face in order to better understand different perspectives and how I may be able to help.

- Point out spaces that aren't accessible and work to make them accessible.

- Learn a basic level of ASL.

The panel concluded by opening the conversation to the audience to share their perspectives and questions.